|

Bright Turquoise Umbrella: Poems by Hermine Meinhard. Tupelo Press, 2004.

Hermine Meinhard is one of my favorite poets. I have watched her beautifully crafted, lyrical poems gain more and more recognition in the years since she became the grand prize winner of Kalliope's National Sue Saniel Elkind Poetry Contest, a contest I oversaw as Kalliope's editor and which was judged that year by Carolyn Forche. In fact, nine poems in this collection were first published by Kalliope.

"Flying," the first poem in Bright Turquoise Umbrella, won Kalliope's Sue Saniel Elkind award. "The project of the poem is to examine perception," Forche, the judge, said. "I was impressed by her [Meinhard's] willingness to risk." Forche's insights explain the unusual poetry in Bright Turquoise Umbrella. Here is a poet willing to risk, a poet whose every poem asks the reader to examine perception.

Read Meinhard in a state of suspended belief, a dream state, a magical state. Connect to her dream state and the poet will provoke truth.

In this world, for example, where pigs speak to little girls, the reader sees the dream, fear, urgency, and the unreliability of the world: "The pigs said to run away, but I was scared, and then they said to hide, so I ran away a little."

In the frightening images of "Yellow Sun," "it's a long day with shoes and chicken soup and running up the aisles of the Food Fair looking for Mother in the twilight on Second Avenue" and finding instead a "long haired man with no face."

In the poem "She Stood," symbols hold fear: "The House was a glass bowl with wind blowing/ the child grew up with difficulty."

And there are beauty and longing: "You went around kissing things. Horses, signs." Sometimes one is "left a tenderness."

These are beautiful, tender, challenging poems.

Hermine Meinhard has taught as resident poet at Prospect Heights High School in Brooklyn and Public School 76 in Harlem. She is now Adjunct Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at NYU's McGhee Division and poetry editor of the literary journal 3rd bed.

Reviewed by Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Kathleen O'Connor. No Accident. Port Town Publishing, 2004.

Dear Max,

Good news! I found a fine story for our next production. It's in a novel called No Accident by Kathleen O'Connor. Ran across a review of the book on a web site, bought it, and found it our kind of murder-mystery.

The main characters are Detective Mitch Gallagher and self-appointed sleuth Tess McConnell. Mitch is investigating the murder of an official of the Rayex Corporation where new hire Tess works. Tess dislikes Mitch at first. But she proves valuable as an investigator and eventually teams up with Mitch to solve the murder. In the process, they fall in love. Their relationship has a number of twists and turns that give fresh play to the old theme that true love is never smooth.

These twists and turns include elements that affect the lover/detectives, drive the story, and, I believe, give it mass appeal:

- the widower who must overcome grief to realize new love

- the battered woman

- dysfunctional families

- sex (the healthy and bizarre kinds)

- job and emotional burn-out

- sterility and ruthless competition in the corporate workplace

- skill and courage in solving a crime

- pregnancy

- the potential for happy marriage and family

Women like me who constantly fight "the battle of the bulge" (and there are many of us out there) will be inspired by Tess. She carries her 183 pounds so well that her lover praises her as a "Celtic beauty" and a "warrior goddess."

Enclosed is a copy of the book. I recommend that we buy this story and turn it into a film. It would also work well in one of our TV slots.

Regards,

Shelly

This fictional note is what a movie scout might write to her boss after reading O'Connor's novel. We certainly agree with Shelly.

Reviewed by Robert B. Gentry

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Lennart Rudolph Peterson (aka Len) (1936 - 2015) was a professor of physics at the University of Florida for 35 years. He was dedicated to his students and the art of teaching, winning several teaching awards. He had a life-long fascination with the sky, took extended residences at the Goddard and Marshall Space Flight Centers, loved observing the stars, and enjoyed walks at night. Much of his spare time was devoted to the writing of poetry, stories, letters, and essays, all of which he included in a bound volume and left with wife and companion of 20 years, Anne Margoluis. Writecorner Press is most grateful to Anne for letting us read her husband's works and publish four of his poems. Sailing the Ship I'm Giv'n, the last poem below, was set to music by Len's son, Gary; Mary Margaret Andrew sang it at Len's memorial service.

Though My Body Resists

TThough my body

normally

resists

intrusion by all

that is not me

and,

as far as

I am aware

obeys most

laws of physics

and of governments,

my spirit moves

in more playful

worlds.

There on a plane

where rainbows

are among

the most

solid

of objects,

and

space

counts

for little,

we remain

with each other

Turning Autumn

The tower bells sound,

and cool air stirs

magnolia leaves

and grass blades

in silent oscillation.

Today our task is to read

the assignment

for at least an hour

cocooned by trees

and each other.

Now the afternoon fades,

and see,

I have read

but six pages

and you, four.

Galactic Wanderings

Your hair ripples

as does a sound

to dissolve in my senses

Your fingers on my eyes

close the loops

of braided poetry

We have come

by cosmic accident

from light years away.

Sailing the Ship I'm Giv'n

Verse 1

I tune to a world

that I live in

learn to sail

the ship I'm giv'n

accept the weaker

sides of me

and focus on

the strengths I see

I am a child

of the land

from mountains tall

to ocean's sand

all nature in

its grand design

I must take care

for it's not mine

Verse 2

With friends I've nurtured

through the years

my help, my solace,

treasured peers

and one I choose

to share my soul

the one who helps me

live my role

I must forgive

who do me wrong

and trust it is

not their soul's song

as well unkindness

I have sown

I must accept

wrong deeds I own

Verse 3

For life is not

a perfect dream

it is an ever

flowing stream

with twists and turns,

some oft unseen

I have a base

on which I lean

And when my life

has run its course

will I look back

with some remorse?

or understand

I made that road

and on it carried

each day's load

Cathryn J. Prince. Shot from the Sky: American POWs in Switzerland. Naval Institute Press, 2003.

This book focuses on the internment of 1,740 American military personnel in Switzerland between 1943 and 1945. A former reporter in Geneva for the Christian Science Monitor, author Cathryn Prince charges wartime Switzerland with:

- shooting down war-damaged American aircraft that entered Swiss air space, killing or injuring some American crewmen;

- applying international law unfairly, giving German soldiers and airmen free rein in Switzerland but discriminating against American airmen;

- violating Article 2 of the 1907 Hague Convention by aiding Nazi Germany's war effort;

- violating the Swiss military code in sentencing Americans to prison without a military tribunal;

- imprisoning American internees who tried to escape into camps as bad as some camps in Nazi Germany.

Prince builds a broad context around her main subject. She includes eyewitness accounts of 25 former American internees and several Swiss citizens, a short history of Swiss neutrality, details about Nazi influence in Switzerland before and during the war, an examination of extremely strained relations between Switzerland and the United States during and after the war, and information on the issue of POW status for American veterans who were interned in Switzerland, a status that the U. S. Veterans' Administration has so far refused to grant.

The author qualifies her criticism of Switzerland by citing examples of humane treatment of Americans who obeyed their Swiss captors. The reader learns that Switzerland was a mecca for Allied and Axis spies; American planes bombed several Swiss cities and towns (including Zurich), killing or wounding a number of Swiss citizens (believed intentional by many Swiss; believed accidental by most American authorities); and the little known fact that by the war's end, 61 American servicemen lay buried in a village cemetery near Bern.

The book's appendix lists the names of over 1,600 American airmen interned in Switzerland, including that of Oscar J. Koeppel of Phlox, Wisconsin (not interviewed by Prince). During the war Technical Sergeant Koeppel of the 773rd Squadron, 463rd Bomb Group, 15th Air Force was the upper Turret Gunner and Engineer on a B-17G piloted by Captain Don Jacobs.

In a recent interview, Mr. Koeppel gave me the following account:

I had 32 missions over Germany and Northern Italy. We knew we had one chance in ten of getting back to base without being killed, captured, or having to land in a foreign area. I had many close calls with disaster. Only my complete trust in God kept me from getting hysterical like some did.

Koeppel then talked about his last mission on December 9, 1944 (the target: Regensburg, Germany); his plane getting damaged; and the crew's decision to fly to Switzerland.

I shot off flares as we flew into Switzerland. No planes came after us. No one shot at us. Jacobs made a wonderful soft mud landing near Altenrhein. No one was hurt. Armed guards marched us to a tavern where we were given beer and pea soup. It was the best food we'd had in months. We played cards and relaxed before a bus took us to Altenboden. The officer in charge of the town gave us forms to send home through the Red Cross letting them know we were safe in Switzerland.

I was in Altenboden about a month. I stayed in two hotels, part of the time under armed guard. The rest of the time we were pretty free to go and come in the town. I attended Christmas Eve mass in a beautiful gingerbread-decorated church. New Year's Eve we had a great party with plenty of beer. Ice skating kept us busy for about a week. Then Don Jacobs, Ralph Mathewson, and I decided to escape. Other guys stayed put. They were having too much fun. I escaped because I wanted to go home and see my wife.

Koeppel's account of his escape is similar to American escapes described in Cathryn Prince's book. He and his two friends used forged passes, eluded Swiss soldiers hunting for them, got help from American authorities and the French underground, and endured a dangerous, bitterly cold boat ride across Lake Geneva to France and freedom. According to Koeppel:

We got pretty good treatment from the Swiss. They were short of food. They took in thousands of refugees and had to depend on Germany for coal and food. Still, I feel I deserve POW status. I was held in Switzerland against my will, and I took a great risk getting out of there. We knew if we were caught we would have a really bad time in prison.

For the most part, Shot from the Sky: American POW's in Switzerland comes down hard on the small, land-locked country. Other books, however, take a much more favorable view: Refuge from the Reich: American Airmen and Switzerland during World War II by Stephen Tanner and Strangers in a Strange Land Volume II: Escape to Neutrality by Hans-Heiri Stapfer and Gino Kunzle. Readers may also wish to consult the internet for information about Americans interned in wartime Switzerland: www.91stbombgroup.com/artfoster.html www.jmi.com/WWII.html and other websites.

Reviewed by Robert B. Gentry

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Muhsin Al-Ramli. Scattered Crumbs. Translated from the Arabic by Yasmeen S. Hanoosh. University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Scattered Crumbs, a novel by Iraqi writer Muhsin Al-Ramli, translated by Iraqi-born Yasmeen Hanoosh, won the Arabic Translation Award given by the University of Arkansas and the University of Arkansas Press. A $5,000 award goes to the author and an equal amount to the translator.

First published in Cairo in 2000, this short novel unfolds through an unnamed narrator living in lonely exile in Madrid. He tells of several generations of Iraqi villagers trying to survive the Iran-Iraq war. These include the narrator's aunt and uncle, their seven sons and a daughter. This village suggests a microcosm of an Iraq torn by war and oppressed by the "Leader."

Not identified by name, the "Leader" is clearly Saddam Hussein, who is responsible for conscripting young and old men, the constant hunting and killing of deserters, the persecution of artists, and the quandary of old men loyal to the country of their birth. One such old man is Ijayel, the family patriarch and the narrator's uncle.

In a heated argument with his artist son Qasim, Ijayel sounds like Rudolf Hess who once equated Hitler and Germany. "The Leader is the homeland and the homeland is the Leader," Ijayel declares.

No, Father, that's TV talk. As for me, I see the opposite, for the Leader has destroyed the country.

Qasim's love for his father and for Iraq find expression in a beautiful painting that Qasim completes before he is executed by Saddam's henchmen.

Ironically, Ijayel gains new understanding and becomes a victim of the brutal power he once revered; Saadi, Ijayel's sodomite son and a former army deserter, ingratiates himself with the regime and becomes head of the League of the Leader's Beloved.

The instances above and many others serve to advance the plot and illuminate meaning as do the author's skillful use of symbols, satire, and dark comedy. All of these elements underscore the story's prevailing moods: sadness and tragedy.

Near the end of the novel, the narrator speaks to his suffering country and to the reader in words that sound almost like a parable:

The seasons of the year do not mean anything to him [Saadi], to us, to anybody.... The changes are here—point to your hearts and draw a circle around yourselves to include the others.

Reviewed by Robert B. Gentry and Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Charles E. Rice. The View from My Ridge. Canopic Publishing, 2003.

Born in the John Ross house in Rossville, Georgia, the late Charles E. Rice lived most of his boyhood at the foot of Missionary Ridge on the Tennessee-Georgia state line. Steeped in Cherokee culture and Civil War history, this area becomes a central metaphor in Rice's much-traveled life, a life richly re-created in this collection of essays and stories.

Rice gives us short, wonderfully lyrical vignettes in the story-telling tradition of Sandra Cisneros's The House on Mango Street. Sometimes profound, always moving, Rice's writings are beautifully crafted. Their intricate designs, almost always completed on one page, reveal the skill of an extraordinary author.

Through Rice's eyes, we see what it was like growing up during the Great Depression and World War II, working in a mill, living in an Oak Ridge shrouded in secrecy during the atom bomb project, and many other memorable experiences. We get vivid insights into boyhood, family life, college life, war, nature, race relations, theology, death and dying, and other important subjects. We sense Rice's epiphanies, are drawn into his contemplations, like this conclusion of the essay "Waiting":

The highest and the toughest waiting is that of standing by without a clue. What the next day might bring; a posture which neither hastens nor contrives the turning of the page of life. When we approach such a posture it is close to faith itself. No longer trying to do something—good or bad—we leave ajar the door of becoming, and our waiting becomes expectancy—becomes us.

The View from My Ridge is an engaging memoir of a progressive minister whose life was touched by hardship, tempered by war, and challenged by the revolutions that have shaped America since 1945. Through it all, Rice struggled to find an enduring truth greater than the shifting values of the society he so ably served.

The form and style of this collection and its remarkable variety and depth of meaning make it a worthwhile and important read.

The View from My Ridge can be ordered through www.canopicjar.com . "The Waiting Mountains," an essay from this book, appears in our Fresh & Ripe section.

Reviewed by Robert B. Gentry and Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Elisavietta Ritchie. Awaiting Permission to Land. A Lyre Series Selection. Cherry Grove Collections, Cincinnati, 2006.

Awaiting Permission to Land, a volume of subtle, lyrical poetry, is poet and fiction writer Elisavietta Ritchie’s fourteenth book. Past readers of Ritchie will recognize and welcome her short poems, always filled with awe at the tiny but significant lives she finds around her – spiders, moths, crabs, fish, gulls, crickets, bumblebees, snakes, mice, dogs, foxes, kittens, chickens, raccoons, and others. And here, too, are larger lives – stags and does and wolves and lovers and great aunts, fathers, and mothers.

All creatures are metaphors for her poetry, as the lead poem in the book describes: “When I walked to the pier you thought/ I’d set off to check for crabs….What I was going for, in truth,/ was to find a poem …/ All I found were these words.”

Ritchie writes of love, death, old age, even Dachau and war, in the imagery of nature – the blackberries in a penal colony unite her to the prisoners who once must have longed for the same lush fruits. Stones in Dachau suggest bones. When almost everyone in a family is murdered, the agony of aloneness is palpable: to escape, leave behind everything, even a kitten.

“Delicate” is not a word to ascribe to her poems. “The Dead Hen Chronicles” begins, “Half the poets I know/have their barnyard tale/ of shattered innocence,” and by the poem’s harrowing end, the reader may turn into a vegetarian.

Ritchie’s poems speak of tragedy, but with such reverence for all living beings that life itself is redemptive. Ritchie knows that “across stratosphere/ and years, that cry from inside/ resounds, resounds.” Some of her poems send out such a cry and readers will hear.

Reviewed by Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Gretchen Roberts-Shorter. Can't Remember Playing. Washington Writers' Publishing House, 2004.

In her novel Can't Remember Playing, Gretchen Roberts-Shorter describes the life of George, a teenage slave in Virginia who is sent by his master to fight against the British in the Revolutionary War. With several other young slaves, George joins a group of white soldiers. He learns to fight and to survive not just the war but the almost insurmountable tensions caused by his light color. When George comes home from the war, he expects to be set free, the right of slaves who fought in the Revolutionary War. His master had told him, "Most likely, y'all could get struck down. If not that, then taken off by the Red Coats....But if you get back, I'll set you free." But the master is not willing to keep his end of the bargain.

Here is a moving story of struggle for freedom about which little is written. We do have novels about slaves fighting in the Civil War, but Can't Remember Playing contains dimensions often overlooked in Revolutionary War literature.

Gretchen Roberts-Shorter's novel offers powerful character development and insights into the mind of a young teen, born into slavery, but willing to fight a war to earn his freedom. The writer's language, at times lyrical in its rhythm and metaphors, amplifies George's struggles: " 'I'm going to be off of this place before the next sun up.' Hindsight became his [George's] friend, so he let it grow until it claimed the space that was left after he'd kicked reason out."

This novel will inspire reflection and rouse your sense of justice.

Reviewed by Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Mark Salzman. Lying Awake, a novel. Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

This profound book asks age-old questions: Does God speak? What is faith?

A Carmelite nun, Sister John of the Cross, thinks she knows God through visions and mystical prayer. Her insights lead to poetry and her spiritual ministry. Then she finds out that her visions, her insights, even her prayers might be the result of epilepsy. Should she allow an operation, she wonders, if it would cure her of seizures but eliminate her visual, spiritual bond with God? If her visions were just brain reactions to illness, how would she survive her long years of contemplation without the direct knowledge of God she thought she had been given?

As Sister John struggles with her faith, the reader gains a fairly accurate insight into the liturgical life of the cloister and a small taste of the problems of living daily in a community of a dozen cloistered women one might never have chosen as friends. This is a book voicing compassion, faith, and reverence.

I, too, read Lying Awake the first time in one sitting, awed by the power and questions of faith, awed by the insights and poetry of Mark Salzman.

Reviewed by Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

All Points Bulletin: Poems by Sharon Scholl. Closet Books, 2004.

In All Points Bulletin, Sharon Scholl leads the reader through fifteen countries as diverse as Tanzania, Tibet, Hungary, and Canada. This ninety-page book offers over 85 poems, all from her literary travel diary.

Each of these poems is a stop in her thirty-year sojourn into what she calls in her introduction "a quest for the meaning of a place."

Many people take photographs on their journeys; the best take photos every half hour or hour and record the unexpected, the ordinary, the usually un-photographed spots and the ordinary people doing ordinary things. Like these best photographers, Sharon Scholl takes verbal snapshots and offers the reader the insights of a poet who is grounded in the arts and culture of the people of the country she visits.

Scholl speaks of paintings, cathedrals, rivers and windmills, castles and Queen Anne's lace, tour guides and cemeteries, roads, lakes, fires, languages, mandalas, and archeologists. Beneath her recognition of place is her insight into its uniqueness, its purification, its delusions, and its point of view. Here are lines from "Amazon Camp, Peru":

Rain on thatch

is not like rain

on tin, wood, shingle

or any human thing.

Scholl is a poet equally at home with a villanelle and an almost limerick. Perhaps the last stanza of All Points Bulletin offers Scholl's sardonic tone, a tone redeemed by her deeper question:

What calls us out beyond our roots

to places often inhospitable?

Are we plain bored silly,

or do we sense some urgency

as deep and sweet as home?

All Points Bulletin follows Scholl's first collection of poetry, Unauthorized Biographies (Closet Books), and two works of non-fiction: Music and Culture (Holt, Rinehart & Winston) and Death and the Humanities (Bucknell University Press). Her individual poems have appeared in literary journals such as Oasis, Kalliope, Northwoods, and Poetry Motel.

Reviewed by Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

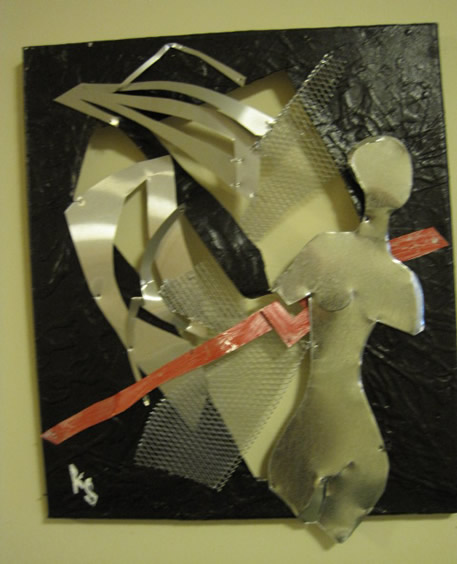

Five Easy Pieces: Complex Constructions by Karl Schwartz

Figures shine, gleam, challenge on canvas. Red bands streak like bolts of lightning. Wall spaces modulate behind metal and colors in simple and complex harmonies of figuration and abstraction. Thus we have Karl Schwartz's latest work as it appears on a prominent wall at Oak Hammock at the University of Florida.

A larger view and an interpretation of each piece follow:

Like the central figures in the other four pieces, the one in this work is made of steel. It's a tree with claw-like branches, roots covered by part of the steel mesh that slants diagonally from top left down to bottom right near Karl's initials. Like the red bands in the other works, this one is aluminum. The opening in the aluminum object (top left) gives the illusion of a person's head and neck in silhouette. White colors splash down black canvas in a striking display of action painting, a technique that Karl often uses.

Here the helmeted, jut-jawed figure conveys strength independent of the other objects. Wall space and black canvas highlight the figure as if it sprang from space to post like a sentinel over its abstract world. Yet ironically it's a partial man with half a shoulder and a long surreal neck. In the foreground an aluminum piece with a swan-like neck spirals from canvas into space and is pinned down by steel mesh running across it--a remarkable interplay of kinesis and stasis. Red touches at the center and near the periphery complement the band's red motif. White speckles the black canvas reminding one of a dark night punctuated by gleams of star dust.

Mesh covers all but the head of the central figure in this piece. The bird looks as if it's just been caught in flight and is staring at pink and silver flourishes that respectively echo tones of the red band and metal objects. The band zigzags--the bird's tail flows into metal--space morphs to vivid forms in a collage of dynamic energy suddenly stilled.

"Fish gotta swim and birds gotta fly," a lyric from Show Boat, the memorable musical. This piece also sings in harmonies: wall space (left) like a placid lake or curving like a drifting cloud from which the fish is swimming/flying, metal figure (top) with split tail as if it were a fish swimming or a bird flying to the red band, metal object (bottom) open-jawed, tack for an eye as if it were a shark bent on prey (sharks gotta eat, too). Animals and objects and spaces all unify in a spontaneous expression of freedom.

Like the helmeted figure described earlier, the woman at right recalls statuary from classical antiquity cast in postmodern form. Viewed one way she looks glued to the red band streaking behind her and to space at her upper and lower body. Viewed another way she looks and leans to the right and pulls space and objects with her. Like shards of Frank Gehry titanium, metals and horseshoe-like space convolute and thrust left, up and away from the woman. Here is paradoxical tension between attachment and escape.

Fine art ultimately leaves us with questions. The red bands in this work obviously serve as unifying devices. What else might they suggest? The artist's passion, his creative spirit? Is the man meant to be some warrior or god in contrast with the woman? To me she appears nude and serene, peaceful and powerful. An earth mother? Interestingly, as originally arranged on the wall the man and the woman stand at opposite ends, between them the tree, the bird, the fish. Might the man represent war, the woman peace, the other figures nature?

This intriguing work may owe much to the artist's subconscious feelings and drives that transcend logical analysis.

For more details on Karl Schwarz's remarkable innovations see his visual essay on this website.

Special thanks to Linda Damico of Oak Hammock for her help with this article's photos.

Reviewed by Robert B. Gentry

Sears, Peter. Green Diver. CW Books, 2009. A full collection of poems published earlier in influential magazines and since revised.

Luge: a chapbook of poems by Peter Sears. Cloudbank Books, 2008. The fourteen poems in this little book are the most recent work, previously unpublished, of Sears.

Reading Peter Sears is like going for long walk with a witty, whimsical, surprising, deeply reflective good friend. Sears first engaged us in The Brink (1999), his Peregrine Smith prize-winning volume. Now we have just finished another fascinating visit with him in Green Diver and Luge.

Green Diver opens with "High in the Bamboo," a brilliant poem of five deceptively quiet stanzas about a cat and the poem's speaker.

The cat likes to sit in the bamboo,

rest its head on its front paws,

and look out at the world.

I like to sit on the porch,

rest my head against the back of my old chair,

and watch the cat look at the world.

These lines move in easy, declarative rhythm with structures that parallel and contrast cat and speaker. The cat sits in nature (bamboo); the speaker sits in a human contrivance (chair). On its front paws the cat gets a fuller view of things than the speaker who at the chair’s back watches only the cat. Animal and human, bamboo and chair, front and back: contrasts that prepare us for tone and action in the rest of the poem.

In the next two stanzas the speaker imposes a game on the situation, tries to catch the cat moving by squinting and feigning sleep. Ironically and amusingly, the speaker falls asleep. The last stanza says:

When I awake, the cat is gone.

I look back into the bamboo.

The bamboo tops move.

The cat and moving bamboo tops suggest being; the speaker’s futile game is doing. The last stanza is mystical, Zen-like. What is moving the bamboo tops? Wind? Cat? The speaker’s mind? It really doesn’t matter. Nature does not think. It just is.

The meditative and playful moods in “Bamboo” anticipate similar elements in many poems in Green Diver and Luge.

Sears follows “Bamboo” with the whimsical “My Emptiness Rides in the Back Seat, Propped Up.” Here is the existential dilemma: emptiness is inescapable. How to deal with it? Humor: “That smile, I can’t take it,/ I threw fresh mints over my shoulder at him[emptiness]/ as hard as I could.” Despair? Severance? “I stop the car, take him out, sit him/ on a wooden bench in the park, and walk back to the car.” Even as the speaker tries to rid himself of emptiness, he cannot escape responsibility for it, “I mean, how long can he last on his own?” No matter what the speaker tries, by the end of the poem, emptiness has snuck back, “There he is, my emptiness …/ waving my car keys.”

In “We Can Help Each Other” the speaker knows darkness; nothing whimsical here: “Darkness that shoots up in front/ of me as if the hood of my car/ flew up in front of the windshield.” The speaker asks to share his darkness with that of the other. But there is no indication the other person will comply. The poem ends with unfulfillment and loneliness, serious chords that Sears sounds in a number of poems.

The poet is equally at home in first or third person. In third person “Postcard to Herself” a self-absorbed American girl “of datebook breeding” shuffles on a beach at Nice, France “sealed in the “pink envelope of herself,” oblivious to nature’s beauty. “Chemo Silver,” the next poem in Green Diver, brings the reader into “the room of tiny killings,/ benign cell, cancer cell,/ leaving your kidneys the chewed socks of God.” Heroically, the speaker resorts to mock apotheoses: “O sperm of death, O sweet sweat of aluminum/…Liquid silver, moon juice, I suck you in,/ Chemo limo, I ride you through the bends.” Vintage Sears!

Three poems show keen insight into the effects of war. Luge’s “Maybe My Head Is an Airport” reflects the feelings of many American boys growing up during World War II: war as play, war as fear, war as duty. Discerning readers will note ingenious plays on words. In “The Iraqi Women” and “Collateral Damage,” women suffer in devastating scenes not pictured in news reports. The formal structures of these poems intensify the horror and destruction of war in today’s world. For example, “The Iraqi Women” unfolds in a subtly modified villanelle whose muted rhymes mourn for the excruciating suffering of women who await “another truck load of the dead.”

In changes of mood and voice, Sears deftly offers many sports images: from baseball in “On My Sixty-Seventh Birthday I Set Out for a Walk” and “My Four Pitches,” basketball in “Air Ball,” sled racing in “Luge” (title poem), rowing in “Instructions to Myself,” and golf in “Acushnet.” None of these poems is just about the sport. Often, the speaker’s knowledge of the sport exceeds his ability to play it. The winner becomes the poet’s imagination.

Another wonderful aspect of both poetry books is the haiku-like lines that appear in many poems. Note the beautiful, lyrical ending to “Instructions to Myself”: “Moonlight may tremble on your oars.” This, after a meditation on being one with nature on the water in a rowboat! Such delicate lines of surprise lift from many of these poems.

Observe Sears, a master musician of sound and image and space in “Just as the High Branch Sags”:

A squirrel leaps

legs V-ed

hits and hangs to

a drooped

bough

that bows

lifts

and calms its leaves

This poem invites comparison and contrast with “High in the Bamboo.” Like many poems by Sears, this one is a fine teaching and learning model, one to inspire all age groups about the art and craft of poetry. Similarly, “The Rain Sounds Like a Delicate Eating” and “On Seeing Your Fine New Book Tepidly Reviewed” convey the wonder and power of poetry. In the latter, the speaker tells an insensitive critic,

…How is

it that someone with so little touch can

wield such public clout? Hey, it’s pleasure

poems breathe in and out. Ask the ear,

the eye, the brain and tongue what they

touch and are touched by.

Excellent writing, poetry or prose, usually reminds us of other writers who may or may not have directly influenced the author. In Sears we hear echoes of Shakespeare, Frost, e.e. cummings, Milton, Shelley, and other important writers, including the philosopher Martin Heidegger. According to Heidegger, we are thrown into the world at birth. We did not choose to exist. We did not choose our bodies or our families. Yet we exist; we are constantly surrounded by the world. Our human condition in the world is being there (German, dasein). Dasein is the condition of constantly moving, changing, thrown into possibility all the time. We are innocent of our thrownness, and we are responsible for how we relate to that thrownness. Though it is difficult for us to grasp our dasein, our anxiety or angst can help us in the struggle to make authentic life choices. (Being and Time. Harper & Row, 1962).

We see certain poems of Sears through a Heideggerian lens. Take “Green Diver” (title poem): the speaker and a companion make the authentic choice to flee an approaching storm but are thrown into the sea and struggle not to drown. In “Chemo Silver,” “To the Care Giver,” and “The Guy Opposite Me in the Chemo Ward,” cancer throws the speaker into the pain of the disease and its treatments. “Care Giver” and “The Guy Opposite Me” also show how cancer throws one into situations where choices and human relations become extremely difficult. In “Accident,” a woman is thrown through the windshield “and dangles across the hood like a dog’s tongue.” In “Air Ball,” a basketball wannabe suffers a painful fall but continues to imagine himself a key player in a real game. In “Luge,” the speaker fantasizes speeding down a bobsled track; thus life is risky, fun, dangerous, angst-filled: “…I love the high/banking in the turns as if the luge is going to/ shoot off the track. Perfect for me: push off/ and pray…./How do you hold on?”

How do you hold on? This is the existential question for all of us. One answer for Sears lies in maintaining traction in life. Interestingly, “Traction” is the heading of Part II of Green Diver. The idea is to pull ourselves through life’s challenges or let ourselves be pulled if that’s the most authentic choice. Traction carries with it a natural angst as shown in the speaker’s reluctant acceptance of death in “Dream of Following,” the powerful poem that concludes Luge. Such tasks and insights require intelligence, imagination, courage, fortitude, humor, honesty—qualities that mark the stellar art of Peter Sears.

Reviewed by Robert B. Gentry and Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Francine Silverman. Book Marketing from A--Z. Infinity Publishing, 2005.

This remarkable compilation of promotional strategies begins with three very important words for authors whether they are self-published or traditionally published: DO IT YOURSELF. Elaborating on this theme, Francine Silverman stresses that promotion of an author's book is his or her responsibility. The help authors get from publishers is usually minimal. To gain substantial audiences, writers must take the time, develop the skills, and sometimes spend money to promote their books 24/7. In Silverman's words, they "need to learn to think like a producer, provide a hook, and entertain an audience in sound bytes, all the while incorporating the ideas from their books to garner sales and more interviews for themselves."

Silverman compiles the strategies of 300+ authors of all genres and arranges them as 35 chapters in alphabetical order for ease of use. We get innovative tips for Advertising, Book Covers, Book Signings, Conferences, Contests and Competitions, Freelance Writing, Newsletters, Pitching the Media, Targeting Your Audience, and many other strategies. In Special Sections experts give insights and advice on 10 important services, including Book Coaching and Consulting, Book Reviewing, Editing, Publishing, and Web Designing.

These sections are followed by More Recommendations from writers of memoirs, biographies, children's books, cookbooks, humor, mysteries, parenting books, and other popular genres. Silverman concludes her tome with three Success Stories: Richard Cote who gets 99% of his income from selling his books and those of other authors through his own publishing company, Corinthian Books; Max Elliot Anderson who published five popular adventure books in 2½ years; Gini Graham Scott, nationally known writer, consultant, speaker, and seminar/workshop leader.

Book Marketing From A--Z is packed with unique ideas from authors hailing from all over the English-speaking world. These contributors present their first-hand experiences with honesty and humor, and Silverman highlights their pleasures and pitfalls in readable blocks.

A particularly effective promotional strategy is that of Joan Wester Anderson. Before she does a book signing, Anderson works closely with the bookstore on Meet the Author posters, fliers, tie-ins with local media, and table displays to assure her signing gets maximum attention the hour or two she is in the store. Her promotions no doubt helped her reach The New York Times best seller list with Where Angels Walk (Ballentine 1992), sell over 2 million copies of the book, and spawn seven more books in what became a series.

To sum up, Book Marketing From A--Z contains a wealth of valuable information for authors, publishers, agents, and others engaged in the promotion of books.

Reviewed by Robert B. Gentry and Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Gerhardt B. Thamm. Boy Soldier: A German Teenager at the Nazi Twilight. McFarland &Company, 2000.

German-Americans are the largest ethnic group in the United States. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, nearly 43 million people claim German as their primary cultural heritage. One of these is Gerhardt Thamm, author of Boy Soldier. Another is my friend Carl.

Carl lives in Wisconsin where German-Americans comprise half the population. My wife and I spend part of the year at her family home in northern Wisconsin. Like many Americans, Carl is interested in genealogy, wants to learn more about his heritage, and is developing a family tree. When he visited us recently in Florida, he said he had traced his roots back to Wurzen. On an atlas, Carl and I pinpointed Wurzen, just northeast of Leipzig.

"One of these days I'd like to go to Wurzen and look up some distant relatives," Carl said. "You know German and traveled a lot over there. Any tips?"

"The closest I got to the Leipzig area was this town," I said, pointing to Tirschenreuth on the map. "My German's very rusty. I haven't been to Germany since reunification. But I've got some things I think will help you."

I gave Carl one of my audiotapes of everyday German words and phrases and an autographed copy of Boy Soldier: A German Teenager at the Nazi Twilight.

"The tape's yours. If you go to Wurzen, you may meet people who don't speak English. Even if they do, they're likely to appreciate your effort to speak their language and learn more about their culture. I'm lending you this book. It's autographed."

"Many thanks! Tape may even come in handy in Milwaukee." He glanced at the book, opened the cover, shut it. "Frankly, I don't see how a Nazi soldier's book'll do me much good."

"Well, do me a favor. Read the first sixteen pages when you get a break at Disney World. When you get back Sunday, tell me what you think. I met Gerhardt Thamm, the author, at a writing workshop. We had an interesting conversation. I learned that he and I were in the same U. S. Army branch, though our paths never crossed in service. I bought his memoir and have exchanged several e-mails with him." I opened the book and took out a note. "Here's some background." Carl read the following:

Gerhardt Thamm was born in Detroit, grew up in Germany 1932-1948, and served as a scout with the German 100th Jaeger Division on the Eastern Front, February-May, 1945. During the 1950s he was an agent handler/clandestine case officer in the U.S. Army's clandestine effort directed against the German Democratic Republic and the Soviet Union. Thamm retired from the Army Security Agency in 1968 and joined Naval Intelligence in 1970. He produced an analysis that saved 320 million dollars in torpedo redesigns, managed human intelligence collection requirements for Navy Task Force 168, lectured and taught at the Defense Intelligence College, and served two years as DIA Intelligence Operations Officer. After his retirement from the government in 1987, he lectured extensively on counterespionage and security measures. His writings include articles in the Armed Forces Journal International; Periscope; Golden Sphinx, The Voice of Intelligence; and the Naval Intelligence Professional Quarterly. In 1994 he received the CIA's award for "Outstanding Contribution to the Literature of Intelligence."

"His credentials are impressive," Carl said, his serious tone quickly turning jocular. "You and Thamm were 'spooks', huh!"

"One legend is an Army Security guy coined the term," I said chuckling. "Seriously, intel people like Gerhardt Thamm did much to stop Communism in Europe. And without a shooting war! I was a tiny part of that huge effort. I'm proud of the bit I contributed."

"Well, I'll give the book a shot, at least sixteen pages." Then Carl was off to Disney World.

A few days later he returned, waving Boy Soldier. "Couldn't put it down. Lost sleep but the read was worth it. Fine book! Expected to see Thamm fighting Russians right off the bat. Almost half the book's about growing up away from the war. Jauer, what a picture-book town! Wonder if Wurzen's like that. Map Quest says Jauer's 86 miles from Wurzen."

"You're talking about the Jauer in Saxony. Thamm's Jauer is now Jawor in Poland. His Jauer before it was hit by the Soviets reminds me of the Germany and Austria I enjoyed the most: the villages and small towns; lovely landscapes; honest, hard-working people; friendly—especially if you try to speak their language—fun; festivals; singing; great beer!"

"What's that beehive-shaped cake he talked about?"

"Bienenkorbe, delicious!"

"Yeah, reminded me of my grandmother...years ago in Wausau. She used to make something like it. When he talked about the sausage and the Christmas celebrations and the pfefferkuchen [ginger bread], thought I was back at grandma's."

"What do you think of his handling of Nazism?''

"Seemed pretty honest about how he and the people fell in line with it. I didn't know there was more than one German attempt to zap Hitler."

"As Thamm relates, a number of Prussian aristocrats and German intellectuals plotted against Hitler as early as 1939. The much publicized attempt on Hitler's life on July 20, 1944 was just another failed attempt to kill him.

"Boy Soldier is consistent with all I've studied about Nazism. Thamm is extraordinary the way he captures Nazi lies, their betrayal of the people, and many Germans' changing attitudes toward the Nazi regime."

"The terrible ordeal he went through fighting the Soviets, just a boy, he and his folks ending up slaves on their own farm!"

"Yes, and he gives keen insight into how awful the Eastern Front was. As bad as the Western Front was, it was mild compared to the horrors in the Eastern conflict. Soviet atrocities were some of the worst of the war. They took the lives of many German civilians, including old men, women, and children. I don't think I ever could have survived what Thamm experienced."

"Reading a book like this causes you to see how naive and sheltered you were as an American teenager. At 15 I ate and slept football. One thing in the book reminded me of my teen self: Thamm's relationship with girls."

"I had a similar feeling reading the book. Incidentally, at 15 I ate and slept basketball."

"Why're you taking so many notes?"

"You're helping me write my review of Boy Soldier. Check our web site when you get back."

"Okay, I will. Better be shoving off."

"Good getting together. Have a safe trip. See you next summer."

Reviewed by Robert B. Gentry

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Solveig Torvik. Nikolai's Fortune, a novel. University of Washington Press, 2005.

Nikolai's Fortune is the story of three generations struggling to survive the rigors of Scandinavian poverty and family tensions. Solveig Torvik divides the novel into three stories, each story told in the distinctive female voice of one family member: a grandmother, her daughter, and her granddaughter. Although Nikolai himself appears only rarely, his mythical journey to America and fabled fortune trigger many of the family's emotional and physical hardships.

The grandmother narrates the most powerful section of the novel: as a twelve-year-old, she leaves her mother in Finland and walks with her tinker uncle the 500-mile journey through the snow, over the mountains of Lapland, to a "better" life in Norway. But life turns out better for her only in that she does not starve to death. In fact, life for the next two generations improves very little. Tragedy builds in Nikolai's Fortune reminiscent of Angela's Ashes. When the story finally reaches the granddaughter's time, she must endure the Nazi occupation of Norway.

Torvik based these fictional voices and many details of daily life in Scandinavian culture on her own family's stories and the information she uncovered doing historical research about her family and the period in which the novel takes place. Nikolai's Fortune fits into the niche of the many fictionalized memoirs now being published. It is distinguished by its subject matter: Scandinavia.

Reviewed by Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Lawrence Thornton. Sailors on the Inward Sea. Free Press. A Division of Simon & Schuster, 2004.

This fine novel by award-winning Lawrence Thornton will fascinate writers who themselves have sailed turbulent inward seas into the minds and emotions of the characters they create. Thornton masterfully guides readers into the inner life of his narrator, Malone, and through him to the circle of Joseph Conrad's friends and fellow writers.

Malone, himself the character Marlow in Conrad's books and Conrad's friend, discovers he is the unacknowledged source of the great writer's plots and characters. Malone says, "I lived in the midst of Conrad's creative ferment, in another man's imagination, my life transmuted before my eyes in an act of alchemy...I wanted to know how he did it, what he felt as he knitted the two of us together and named the product Marlow."

But even more intriguing is the novel's voyage into the mind of the petulant and profoundly introspective Joseph Conrad, author of Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness. Conrad tells Malone, "I used you to tell the story of my mental life, Malone. You allowed me to say what I thought. For the first time I was able to hear myself, and learn my own truth."

Integral to this story are questions of friendship, integrity, loyalty, and creative inspiration: Does an author have the right to re-create the inner lives, decisions, or emotional states of his friends? Does the real life character have a right to destroy the imagined life? And in this question lies the subplot: the story of English Captain Fox-Bourne and the sinking of a German U-boat.

Lawrence Thornton appreciates the finely nuanced feeling, the turned gesture, the right word. "Powers favored me with a vision of Conrad disappearing into the weave of ropes and masts and I couldn't help but wonder if he had known that death's hand was resting on his shoulder. If he had, had that contributed to his need to tell me his story, get it off his chest before it was too late?"

Even if one is not overly familiar with Conrad's books, Sailors on the Inward Sea stands on its own as a fine sea yarn, a mystery, and a poignant tale of war's moral dilemmas.

Reviewed by Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

Katherine Vaz. Mariana. Aliform Publishing, 2004. This novel was originally published in the United Kingdom and has been translated into six languages.

Mariana, the novel, is based on the true story of Mariana Alcoforado, a 17th century nun who has a torrid love affair with a French mercenary during Portugal's struggle for independence. After she was abandoned by him, her passionate letters to him became famous throughout Europe during her lifetime.

Her influence persists even to this day. Artists including the poet Rilke and the novelist Stendhal as well as the painters Matisse, Modigliani, and Braque have all had a part in making the nun Mariana into one of the world's greatest romantic women.

Katherine Vaz begins the story with a head-strong little girl who defends her brother using a lute as her sword, not a stick, because "a lute was beautiful and a stick was nothing and Balthazar had to be defended by a beautiful weapon." Such romanticism and wild energy follow Mariana from her father's house into the convent where her rich father pays for her protection during Portugal's wars for independence.

Mariana becomes a nun, then falls for one of the soldiers roaming Portugal. Her famous letters attest to her all-consuming romantic love, nurtured for the rest of her life in the convent even though her lover never returns. After doing thirty years of mandated penance for her love affair, Mariana is not bitter. She explains, "I wanted to feel sorrow as deeply as I feel love." Though abandoned in love, Mariana, through Vaz, becomes a redeemed figure.

Here is a book poignant with details of an almost unbelievably tenacious commitment to love, a love made more intriguing because it begins and survives inside 17th century cloistered convent walls.

A poet herself, Vaz tells a famous story, making it believable through specifics of the time and place. But the power of this book is the magnificent language of the poet. Vaz's cadence and narrative style match the power of an almost mythical lover whose letters and love have traveled from the 17th century cloister to us.

Reviewed by Mary Sue Koeppel

Table of Contents | Home | Top

|