|

John (Jack) Clements and his wife Cynthia are founding members of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. A retired clergyman, Jack served for 40 years in American Baptist and community churches. As the minister’s wife, Cynthia provided important support to her husband’s ministry. She also taught early childhood special education. Jack and Cynthia are engaged in many Oak Hammock activities. Cynthia is a regular writer for the community’s newsletter, The Oak Leaf.

CYNTHIA

We lived in the village of Alfred. It’s a town in western New York near the Pennsylvania border. We had a family farm nearby. I recall ration booklets for gas and sugar. We didn’t have too much trouble getting gas. We got about all the meat we wanted. But there was a shortage of sugar and butter. This was a disaster for me. I was a teenager and I wanted to bake cookies, cakes, and other things. We saved fat and collected scrap metal, mainly tin and aluminum cans, and scrap rubber. We even donated used toothpaste tubes. We’d put all these things out at curbside and somebody from the government would come by and pick them up. We made our own soap—it was awful stuff! We also bought war bonds.

Even in a small area like Alfred, there were people killed in the war. I remember Gold Stars on windows. I remember the blackouts. At night we had to pull down black-out shades. If any light showed from our windows, a Civil Defense patrol would come by and tell us to black out the light. I was a plane spotter. We volunteered to go up on a tower at the university and watch for planes. If we saw any, we had to identify them from a chart. I only saw a couple of planes and they were so far away I couldn’t really identify them. Naughty me, I think I fudged an identity.

I was in high school during the war. In most towns and cities there was shortage of boys and young men for girls of dateable age. I was lucky because many guys were in the Army Specialized Training Program at our local university. I was only about 15 years old, but my usually strict parents let me date some of these men. It must have been their contribution to the war effort.

JACK

I grew up in New Haven, Connecticut. I was raised in the American Baptist Church—that’s a whole lot different from Southern Baptist. Protestants and Jews were minorities in our community where there were mostly Irish and Italian Catholics. I got severely hurt playing football in ’43. Two big guys on the opposing team were told to take me out and they did. I had blood transfusions. My knee was banged up really bad. I was 4-F. I played drums in a college band, and we entertained at USO clubs around Connecticut. Many college females were bused in to dance with the military men. My great grandfather William Hasse had been Burgermeister of Berlin. My grandfather had been in this country 20 years and was a citizen, but the FBI investigated him. They asked him what he was doing for the war effort. He said he was working for High Standard Manufacturing Co. making .50 caliber machine guns for B-17s and other bombers.

I was going to New Haven State Teachers College, now the University of Connecticut. I really wanted to contribute to the war effort. My grandfather got me a summer job at High Standard. I worked in the Shipping Department double checking serial numbers on machine guns before they were shipped to the Army Air Force to be used in their combat planes. The guns were oiled down with Cosmoline. Cosmoline got all over your hands and clothes—almost impossible to clean! I worked the night shift and slept in the daytime. A number of women worked in the plant, mainly in the packaging area.

How did women without technical skills adapt to the plant machinery? I also wonder how they juggled work and family.

Most of the women did non-technical work like packaging so they didn’t need a technical background. Few had to juggle family and job. Some were there because they had sons in the war and they were older and their kids were out of the nest. Others had husbands and sweethearts in the war and they were younger. As I recall, few of these younger women had children at home.

I went to a large high school in New Haven—1,000 in our graduating class. Two hundred of those were killed in the war. The son of close neighbors of my family was killed very early in the war. His parents were Irish immigrants, very hard working and patriotic. Two of their other sons subsequently volunteered for the service as they came of age.

How did these tragedies make you and those around you feel then?

We didn’t give into despair. We kept hope very much alive. We had a religious sense that our faith would see us through the war. People worked together, supported each other. When somebody’s son or father was killed, they got a lot of support from friends and neighbors. When I was hurt, I got great comfort and support from so many good people. That was a major reason I decided to become a minister. I wanted to give back, to help people.

Before the war many wanted to stay out of the fighting in Europe. Pearl Harbor changed that.

John R. (Bob) Denny grew up in Trenton, FL, graduated in accounting from the University of Florida, and retired as a public accounts auditor. He is a founding member of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. Since 1994 Bob has been chaplain of the United States Forces in Austria Veterans Association, and the organization's 2002 reunion book was dedicated to him. He is also a long-time member of the American-Austrian Cultural Society. His story below spans the years 1939 - 1946 when he came of age as a civilian and a soldier during World War II.

I was 13 when World War II began in 1939. Two years later I was like the rest of America, shocked and angered by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It wasn't long before rationing became government policy and we had shortages of gasoline, tires, and food, especially meat. German submarines attacked merchant ships off the coast of Florida. I remember attending the funeral of a merchant seaman. His ship had been sunk by a German U-boat, and his body had washed ashore on the beach near Jacksonville. This seaman left a widow and small children. He was the uncle of one my classmates, Betty Sanders May. About this time I heard news that the brothers of some of my classmates had been killed in battle.

I was 17 when I enlisted in the Army in 1944, one week after D-Day. I had five months of infantry training, a lot of it at Camp Blanding, Florida. I was the fourth generation of the Denny family serving our country during wartime. My father's Uncle George Denny, his older bother John Denny (my grandfather), their father Benjamin Denny had served in the Civil War, and my father, Benjamin Denny, Jr. had served in the First World War.

My platoon was training to be radio operators and learning Morse Code. At the same time we were put through much physical and weapons training, calisthentics, marching and running double time, exercising with power poles, firing and qualifying with the M-1 rifle and firing all the weapons that an Army company uses. We were also put through gas-attack training with gas masks, walking under artillery fire, crawling under machine-gun fire and shown the use of flame-throwers. The Army thought the war in Europe would be over soon, so I was being trained to fight the Japanese. I was trained to use a bayonet and thrust it in an enemy so that it could be jerked out and not stuck in the enemy's body (on Veterans' Day 1999 I gave a talk to Social Studies students at Bell High School in Gilchrist County, Florida. I showed them how to use a bayonet against an enemy soldier). My platoon's scheduled training period of 17 weeks was shortened to 15 weeks. I got two Military Occupational Specialties (MOS's): Infantry Rifleman and Radio Operator, Slow Speed.

Private Bob Denny in the front yard of his parents' home in Trenton, Florida, 1944

Because of the Battle of the Bulge, my training was cut short and I was sent to Europe. We shipped over on the S. S. Santa Rosa. It had been a Grace Lines ship that was converted to a troop ship. Although I was a private, on ship I was a “salt-water sergeant.” That was kind of an acting NCO. I took care of bunk assignments and billeting in my ship area. We landed at Le Havre, France, and took a 40 and 8 across France into Germany. It was one of those old World War I French trains that carried 40 men and 8 horses. It was the same kind of transport my father had ridden in France during the First World War. Couldn’t believe they were still using those things. (Chuckles.) A bunch of us slept in the baggage area. It was more comfortable. We could lie all over duffel bags and sleep better than sitting up like a lot of them did. We were on the train over two days. No toilet facilities! We did number I out the door. We held number 2 till we got to a French town—forgot the name. We stopped at this train station and boy did we line up for the toilets in a hurry! Anybody who’s used a French toilet will tell you it’s quite an experience. (Laughs.)

We rode into Germany in a truck. My M-1 rifle was issued to me on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945. By the end of the week I was assigned to the 165th Combat Engineers. I had been given no training as an Army engineer and no special training to fight the German ideology of their being a master race of people. I knew nothing about the building of bridges or the handling of road machines and heavy equipment.

At times we saw German jets and observation planes flying overhead. One time while riding on the Autobohn, we got to see close-up a German jet which had landed near this super-highway system. At that time we Americans had no jet airplanes. When the German observation planes flew overhead, some men in my company got their M-1 rifles and shot at them, but they did not hit any. If we heard the sound of aircraft bullets hitting the ground, if it was possible, we tried to take cover. Foxholes were considered a possibility, but we kept on the move too often. I remember us driving through this spa town, Bad Kissingen, and seeing German soldiers walking on the sidewalks. They didn’t look at us. We looked at them but not long. Nobody shot at anybody. Bad Kissingen was where a lot of German wounded were being treated.

We went through Nürnberg and found it devastated. We were ordered to build a reviewing stand in Nürnberg's Adolf Hitler Platz. The purpose of this was so some American general could claim the American Army had a parade there on Hitler's birthday, April 20, 1945. German snipers started shooting at us, so the construction of the reviewing stand was delayed. But we were able to build it in time to have the parade one day after Hitler's birthday.

Munich was another devastated city we went through. Nearby was the Dachau death camp. We went through Dachau early in May, a few days after it was liberated by the American Army. We were there only a couple hours. I saw a dead German officer without a leg and his crutches lying on the ground. His blood had mixed with the snow. I suppose a bunch of prisoners had killed him. I saw other bodies on the ground. The worst thing I saw was a train parked at Dachau full of the dead bodies of prisoners. The picture on the left here shows corpses strewn in one boxcar. I remember seeing the body in the picture on the right. I got this picture years ago, xeroxed it, and put in my World War II album (the American soldiers aren't from my unit). I'll never forget the horrible things I saw at Dachau.

[These Dachau death camp pictures are taken from a Bing image search]

After Dachau, our unit rode on the autobahn into the alpine region of Bavaria. We observed the mass surrender of German army units. We rode on one side of the autobahn and Germans in trucks rode on the other side. Each of their trucks was flying a white surrender flag. At Berchtesgaden, our company commander with a Swiss German last name, Fred Fluckiger, let us take trucks up to Hitler's house to see it. We got out of the trucks and walked a short distance to the house. I know it had been a nice place because I bought a slide picture of the house when I visited

the Berghof, Hitler's home in the Obersalzberg of the Bavarian Alps near Berchtesgaden. All of the buildings in the area of his house had been bombed. There were no rugs on Hitler's floor; there was no floor except the concrete underneath. The wood was all burned off. I got to stand and look out the window where he must have gazed before when he made decisions there. I found the steel piece that held the strings to his grand piano. It was cracked. I broke off some of his piano wires and I also got a piece of glass from his big

window. The kitchen floor was covered with broken dishes. I suppose one of his cooks even had potatoes in the pot ready to cook. I remember looking in the pot of potatoes and saw they were scorched. Apparently, the cook left in a hurry.

We arrived in Austria on May 5. Three days later we celebrated V-E Day in a wooded area next to the autobahn in Salzburg. This place was near the airport and we could see the Untersberg Mountain. Its peak rises over 6,000 feet. We spent a month in this wooded area, and again we slept in pup tents. In this picture I'm standing on the autobahn by our encampment site in May of 1945.

We had Army chaplains of various faiths. I remember that in Salzburg, we had a religious service out in the open, under the trees, in thanks for the end of the war in Europe. When we moved into Innsbruck we lived in apartment houses. This was the first time I slept with a roof over my head since I'd arrived in Europe.

Innsbruck is just north of the Brenner Pass. One Sunday afternoon we drove to Brenner and then walked a few feet into Italy. We saw many displaced people. They were trying to find their way back to their homes. While we were in Innsbruck, we saw many Italians carrying their belongings on their backs as they walked along. Around this time I was transferred to the 31st Engineer Battalion in the Reutte area of Austrian Tirol. I met Clayton Ellison, who was in this unit. Clayton was from Wilcox, Florida. We attended a bridge school at a place on the Danube River in Germany. After that we returned to Austria and spent some time in a beautiful lake region east of Salzburg. In this area we visited an underground factory where the V-2 rockets were assembled. In this part of Austria we helped supervise the rebuilding of the damaged railway system.

We went from Salzburg to Vienna. Vienna had been overrun by the Soviet Army, and we entered Vienna through the Soviet Zone. As we travelled in convoys on the road to Vienna, we saw troops with slant eyes; they were Mongolian soldiers in the Soviet Army. We also saw Hungarian refugees on their way home. Vienna and Austria were divided into four zones then, similar to the division of Berlin. The armed forces of Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States occupied Austria. Some American military authorities wanted to establish a separate political government in the American Zone of Austria. This would have resulted in two separate and different governments in Austria as in East and West Germany. Fortunately, Eleanor Dulles, who was the sister of John Foster Dulles (later Secretary of State under Eisenhower), stepped in at this time. She suggested to American authorities that if they set up a separate government, this would be disastrous for the Austrian people. The American military then decided on one government for Austria to be determined by free elections. I saw democracy restored in Austria and wrote home to my parents about it.

The women in Vienna were still suffering from the effects of war and because of their lack of male companionship, they became most fascinated by us Americans. It was easy to pick up girls on the street at night. On one occasion I accompanied a fellow soldier into the Russian Zone of Vienna to spend the evening with a couple of girls. They had very little refreshment to offer; all food items were very scarce. The visit in the Russian Zone was most uncomfortable, especially when returning to the American Zone in the late hours of the night.

What were some of the highlights of your time in Austria ?

• One was attending the Labor Day Festival Concert in Vienna on September 3, 1945 to celebrate the end of the war. At this concert I heard the famous Vienna Boys Choir. I also heard Elena Nikolaidi, the famous Vienna Opera star, sing an aria. Years later she came to America and sang with several opera companies and taught at Florida State University. I had the good fortune of meeting her on Labor Day 1995, fifty years after I'd heard her sing in Vienna, and we ate lunch with a mutual friend.

• In a small garden I picked an Edelweiss flower, pressed it between paper, and sent it home to my parents. They kept it for me, and I now have it framed under glass, this "Noble White" flower.

• At Zipf, about 20 miles from Salzburg, I walked into an underground plant where the notorious V-2 rockets had been loaded with liquid oxygen. I saw many of the propelling tail assemblies of the V-2 rockets.

• Our unit was charged with building a parking lot for the Headquarters Building of the United States Forces in Austria.

• The Austrian people needed something to burn during the winter. Very little coal was available. So my unit supervised the cutting of wood from the famous Vienna Woods so people could heat their houses in the winter.

• I climbed to the roof of the Hofburg Palace to help erect the main flagpole that would fly the flag of the country whose forces would lead the administration of Vienna and its First District. Each country would alternate on a monthly basis as leader of this administration.

• We heard talk that during meetings between high-level Soviet Union and American officers arguments sometimes ended with fist fights.

• Ernest L. Sanders was in my Army unit. When I was at Bell High School to talk to the students, I met Ernest's sister and learned that he was deceased. We had a long talk and shared remembrances about Ernest. It was a wonderful and fulfilling conversation.

What was your highest rank?

I stayed a private for a while because the war was ending and a lot of rank was frozen. I was transferred from the Engineers to Vienna Area Command Headquarters and worked for Major Buder in the JAG section [Judge Advocate General]. He promoted me to Private First Class and then to Technician Fifth Class (T/5). A T/5 then was equivalent in pay grade to a corporal. I got discharged at Fort Bragg on August 6, 1946.

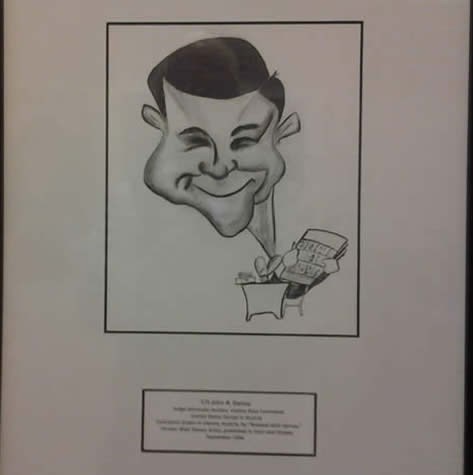

Once when a bunch of us were having a good time, a Stars and Stripes artist did a caricature of me:

The caption reads:

T/5 John R. Denny

Judge Advocate Section, Vienna Area Command

United States Forces in Austria

Caricature drawn in Vienna, Austria

by "Relaxed with Syntax"

Former Walt Disney Artist;

published in Stars and Stripes

September 1946

Bob Denny's military decorations:

European, African, Middle East Service Medal With Two Bronze Stars

World War II Victory Medal

Army of Occupation Medal, Germany

Good Conduct Medal

Marksmanship Badge 30 cal rifle

|