|

Kirk and Gloria McDonald resided for many years in Coral Gables, Florida, where he practiced law in a prestigious firm, she taught English and Reading in the city's school system, and they raised three children. Founding members of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida, a stellar retirement community in Gainesville, FL, they now have six grandchildren. In the following story, Kirk tells of his service in the U.S. Navy and concludes with some details about his law career. He holds two Korean Service Medals, one from the South Korean Government and one from the U.S. Government.

Why did you join the Navy?

During the 30's I remember airplanes flying overhead from the Cleveland, Ohio's Hopkins Airport and wondering where they were going. Later, I went to the annual air show there and observed parachutists jumping from planes over the field. When I was about to go into college at Miami U. in 1948, my older brother, Jim, urged me to join an officer training unit (since he had been an enlisted man in the Army Air Corps during WW II). I joined the NROTC and was laughed at by the other students during our weekly drill sessions. Then came the Korean War and many of my fellow students got called up to serve in the armed forces. It was an annual custom during Spring Vacation at college to go to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida . But I went to nearby Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, to hitch a military flight since I was wearing my midshipman uniform. After a two-day flight, I climbed into the cockpit of a two-engine Beechcraft and we flew up through the clouds. It was the most beautiful sight that I have ever seen, bright sunlight in the winter months!! We only flew to Atlanta. Then I got a Navy flight to Miami. We flew low over the coast of Florida.

Upon graduation in 1952, I was assigned to the USS Bataan Aircraft Carrier CVL-29, which was stationed in Sasebo, Japan. When I arrived in Japan to go aboard the Bataan, there was nobody to greet me since the squadron had been dispatched to a local airfield while the Navy painted the waterline of the carrier. This meant tipping the ship from side to side to allow the painters to do their job. I was assigned temporarily to an aviator's room. I then put on my "Captain Hornblower" look and walked up to the empty flight deck to inspect the harbor view of Sasebo, Japan. There was a stiff breeze blowing across the bow when I lit my pipe and faced the breeze. After a few moments a chief petty officer came down from the bridge unto the flight deck to advise me that "there was no smoking allowed on the flight deck!" I managed to find my quarters where I stayed the rest of the day until the Liberty Bell rang.

Since I had no duties, I went to the gangplank and got aboard the officers' gig for transport to shore. On the way in, I met another young officer who was acquainted with the local club. We had some Brandy Alexanders, a drink I never had before. Soon we were drinking with some British officers who invited us out to their ship for dinner. It was the flagship cruiser of the fleet. Our hosts excused themselves to dress for dinner while we drank some more beer in our short sleeve khaki outfits. Finally, the British officers all came in dress tails! We had a formal dinner served by their Marines. Then the captain invited us to watch a new Alec Guinness movie.

About 10 p.m. their officers' gig took us back to the anchored USS Bataan after some signals were exchanged. When we arrived, our executive officer had been awakened and was waiting at the gangplank to meet the "dignitaries." When he saw the two bedraggled ensigns, he asked who we were and what we wanted. We explained who we were the best that we could. He told us to go to our Rooms. I then asked for some help to find my room. (Chuckles)

What was the mission of the Bataan and what were your duties on it?

I was assigned to the Damage Control Division aboard the Bataan. The ship took turns with another carrier in operating in the Yellow Sea off the coast of Korea every nine days. We had U. S. Marine pilots flying close air support to the UN troops fighting in Korea. My duties on the Bataan were in the engine room. I didn't see the light of day for several weeks. I told the captain in my initial interview that I had placed my request for pilot training before I left college. Also, I thought that ship assignment should be topside where I could observe the flight activities. But I was assigned to stand watch in the engine room and had to inspect the bottom of the ship every week or so. That meant climbing down several floors (decks) until I got to the keel of the ship. Of course, that is where everyone stored their stash of personal items they were taking back to the states.

I was finally assigned to Flight School at Pensacola, Florida. I underwent Basic Training, Formation Flying, Instrument Training, Night Flying, and Carrier Landings. BUT every Friday we went to the Officers Club at the main base to celebrate our survival during the past week and to meet the few single girls living in Pensacola.

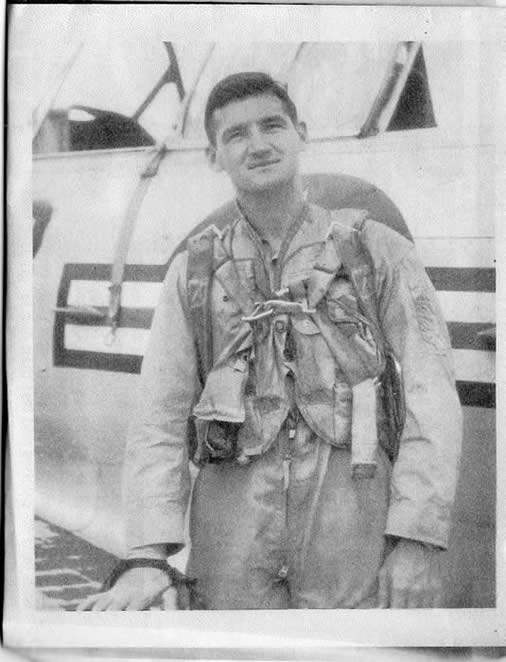

Kirk McDonald in Flight Training

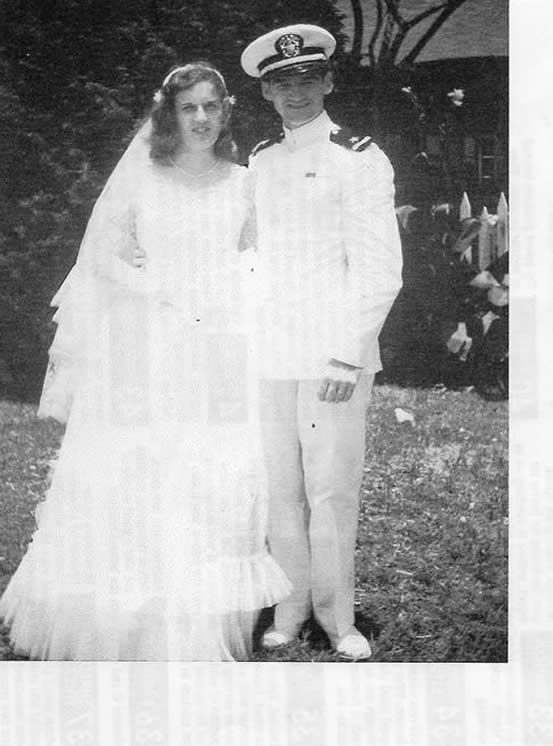

My college sweetheart, Gloria, consented to marry me while I was in carrier training so we had a real military wedding with white dress uniforms, swords and a military chaplain Catholic priest who had never married two Catholics.

After a short honeymoon in New Orleans, I had to wait several days before going for qualification. Then I was informed that I had to go aboard the carrier in Pensacola where I waited five more days without flying an airplane. My first landing was so smooth that I thought the rest would be a piece of cake. The second landing was so hard that both tires BLEW! They dragged my plane to an aft elevator where after I got out I threw my helmet across the Ready Room since I knew that I would have to go back for retraining. But all of a sudden they called my name on the loudspeaker to fly another plane. After two more landings the plane needed gas. I didn't get a third plane till later in the day. I was the last plane in the pattern to get two more landings. When I got back to the Ready room they were calling me to find out where I was. When I told them I had landed successfully 6 times, they asked me what I intended to fly, I said, "Helicopters." (Laughs)

When I finished flight training, the Navy sent me Corpus Christi where I qualified in seaplanes. Then they sent me to the Naval Air Station on the Patuxent River, about 60 miles south of Washington D.C. I was assigned to a new multi-engine land squadron that included World War II veterans. We flew barrier patrols up and down the Atlantic Coast, all over the Caribbean and up in Nova Scotia. We also flew on operations with the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean Sea, and all over Europe.

We soon got new Connies from Lockheed Aircraft. A Connie is a big triple-tailed aircraft with a large radar dome on the top and one on bottom of the plane. Lockheed developed the Super Constellation for commercial purposes with four reciprocal engines and three vertical stabilizers. The plane was modified to have a large fiberglass structure on top of the fuselage which held radar antennae to measure the altitudes of other aircraft and it had a large fiberglass structure (like a swimming pool) on the bottom to measure distances of other aircraft and sailing ships. It held about 11 bunks, 10 or more radar operator stations, a booth which held at least four to eat, a kitchen grill, a radio operator station, a navigation table with a Loran positioning device and extra seats for the five pilots. It had electronic gear in the nose.

What was the Super Connie's mission and what were your duties on the plane?

We conducted airborne early warning for Russian planes flying off the east coast of the U.S. I alternated flying the plane or navigating with the other five pilot-navigators. There were another 20 people running the radar operation.

Did you ever spot any Russian planes?

We saw no Russians, heard no Russians. We played war games and directed fighters from an aircraft carrier in the Med to take off as a "friendly" and then directed another fighter as a "boogie" to be intercepted some place over Corsica or Sardinia. Then we went home for dinner in Naples, Italy. We also flew whiskey runs to Argentina, Newfoundland, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and Bermuda for party functions. Fortunately, we flew to Naples, Italy, every six months or so to work with the Sixth Fleet. That included stops in Iceland, England, France, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Spain, and Algiers for gas, motor scooters, marble tables, leather goods and other goods. The wives were always anxiously waiting for our return from overseas.

When we were not flying special missions to Europe or running whiskey runs to Bermuda, we had to protect the East Coast of the United States. Unfortunately, I lost three friends in different training flights (carrier landings and mid-air collision) or while out on patrol over the Atlantic.

The Navy sent me to Naval Justice School in Newport, Rhode Island, so that I could try a few cases while on active duty. I got discharged in Dec. 1955 with the rank of Lieutenant (equivalent to a Captain in the Army). Then I flew in the Reserves for three more years (all kinds of airplanes) while teaching math in a local high school and going to law school at night. I graduated from the University of Miami Law School in 1960, took the bar exam, and started practicing law with a Coral Gables law firm. My partners in this firm included a U.S. Congressman, the Mayor of Coral Gables, the president of a bank, and a newly elected President of the Jaycees. So I had lots of trials appeals and divorces to handle.

My Navy service and law career were great experiences.

Roman Menting is a lifelong resident of Phlox, Wisconsin, a retired master plumber, and a member of the American Legion. He and wife Eileen are regular communicants in Phlox's St. Joseph Church. They have five children (one deceased), nine grandchildren, and three great grandchildren. Roman was Grand Marshal of Phlox's 2012 Memorial Day Parade, one of Wisconsin's largest annual Memorial Day celebrations. During the latter days of World War II he soldiered in the 38th Infantry Regiment of the Army's Second Division. After the war he served in the 14th Infantry Regiment, 71st Division.

I was drafted and did basic training at Camp Blanding in Florida. It was in the winter of '44-'45. Got real chilly at night. By noon we were doing long hikes, sometimes as long as twenty miles, with full field packs. The sun was baking us. I remember the sweat running down my back. That was no place to live. There were a lot of Southern guys in my unit. Six were named Moody. (Chuckles) Don't know whether they were from North or South Carolina. They were pretty good guys. Did what they were told like all of us. Couple of them couldn't read or write too well.

What weapons training did you get in basic?

The M-1 rifle. We all used it. We shot at stationary targets. We trained on the 30 caliber machine gun. Most of the time the machine gun bullets were blank. We got instruction on bazookas. Only a few of us fired them. Can't remember whether I fired one or not. I never threw a live grenade. Training in grenades was mostly lecture. They put us in a room and turned the poison gas on. We had to put our masks on quick and put 'em on right. One guy didn't and fell down. They got him out of there or he'd have died. Toward the end of basic training they put me in the motor pool.

My older brother was killed while I was in the Army. They gave me six months leave. I went home and worked in a lumber camp for a guy named O'Brien. I couldn't work just any civilian job. You had to do something necessary for the war. That's why I got in the lumber camp, and it was real hard work. Robert was missing in action a long time before we finally heard he'd been killed. There was talk he was killed by "friendly fire." My sister Margaret has details on that. *

How did you feel when you heard he was killed by "friendly fire"?

I was mad, but I got over it. This is the kind of thing you gotta get over or it'll mess you up. I have a list of prayers I say every day. One is for Robert.

When did you get to Europe?

My outfit left the U.S. April 23, 1945. We rode across the Atlantic on the Santa Paula. It took thirteen days. We were one of nine troop ships. The whole convoy was about fifty ships. A lot of men got sick. They'd run to the side of the ship and puke over the side. Some puked when we hit shore. I never got sick. I learned not to eat too much. Best to eat fruit if you could get it. We landed at Weymouth Harbor in England in early May. That night we crossed the Channel. All kinds of bells started ringing while we were on ship. We found out the war had just ended. We stayed a few days in La Havre, France. Then we got on a 40 and 8 and rode into Germany You know what a 40 and 8 is? (Chuckles)

A train boxcar carrying 40 men and 8 horses. My Dad experienced it in World War I. What were your duties in Germany?

We were just in Germany a week and stayed at a German officers' depot. Then we went to Czechoslovakia May 20 to guard German prisoners, 1400 of them. I remember standing on this big hill near Pilsen. It was very cold. We had rifles but no ammunition in them. I guess the Army felt the Krauts were no longer a threat. We just stood there on the hill, holding our rifles, watching them. They had nothing but their clothes and those big gray overcoats they always wore. We let 'em go up on the hill and gather wood and they made a bunch of fires to keep warm. They looked pretty whipped, like they felt they'd done all the fighting they could do and now it was time to go home. Of course we wanted to go home, too.

How did you find the Czech people?

We didn't see many Czechs. We stayed mostly in rural areas, small towns. I saw farmers going out with their tools to work in the fields. One family was very nice and gave some of us food. I don't recall what it was. We slept in Czech barns and got lice, so we had to move out and sleep in yards. We couldn't speak their language and they couldn't speak ours, so there was little communication. I was with a guy from Fond du Lac [Wisconsin] and we went to a brewery. We had big schooners of Pilsner beer. I tell you, that was fine tasting beer.

We left France on July 13, 1945, sailing on the Monticello. There were 7,500 troops on that ship. We landed in New York on July 20. I didn't get off the ship till the next day because my unit was the last one off. After that I served mainly at Camp Swift in Texas and Camp Carson Colorado. They were getting us ready to fight in Japan. Coupla weeks later the war in Japan ended. I always say my brother Robert did the fighting for me. He saved my life.

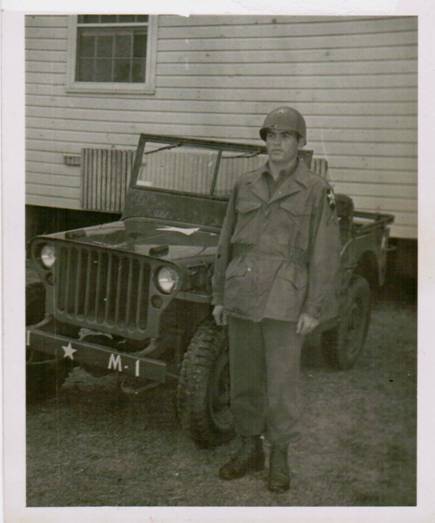

They kept me in the Army another year. I worked mostly in the motor pool. Here's a picture of me at Camp Carson. They told me to stand at attention while some guy took my picture. I got commended for having the best looking, cleanest jeep in M Company. They even made me acting tech sergeant. (Laughs)

I got several furloughs. It was good to get home. If I was there very long I had to work on the family farm. That was harder work than the Army. (Laughs) I finally got discharged on August 6, 1946. My Army life was 1 year, 8 months, and 8 days.

* Margaret Menting's account of her bother Robert's death follows.

Margaret Menting, the sister of Roman Menting, whose story precedes hers, is a retired educator. She spent most of her long professional career in California and Alaska. She has been involved in a number of charitable organizations and has travelled extensively on all continents except Africa. Recently she has been promoting Fair Trade Coffee. Margaret recalls hearing details about her brother Robert's death in World War II.

My brother Robert Menting was drafted into the Army in 1942 and served with the 314th Regiment, 79th Infantry Division. The Army said Robert died of a shell fragment wound to the back of the head. My mother recorded this information on a slip of paper. She apparently got it from the Army:

Menting, Robert Sgt.

Grave No. 1113, Row No. 21, Plot H.

Date of Death 23 Oct 1944

Place of Death Vicinity of Embermenil, France

Date of Burial 31 Oct 1944

Time of Burial 1505 hrs.

Religion C.

I remember Tom Duffy coming to our house and telling all the family what really happened to Robert. Tom lived in our area. He had been in the foxhole with Robert, and he still had shrapnel in much of his body. He said Robert's unit was being pulled back for R & R and a new bunch from the 44th Infantry Division had come in. This 44th group was ordered to fire at the Germans but one shot was too low. It killed Robert and wounded Tom. A chaplain got them both out of the hole. Robert was hit in the back of the head. This meant the fire came from the American position.

This chaplain wrote my mother a letter about Robert serving as an acolyte at mass shortly before he died. The chaplain remembered talking with Robert about the war and Robert saying, They'll never get me. Our family feels this was the chaplain's way of suggesting that Robert was not killed by the Germans but by American fire.

My sister Mary Ann Bauer did considerable research on Robert's regiment. After she died I inherited some of her materials, including a history book on the 79th Infantry Division. The 313th, 314th, and 315th Regiments of this division were involved in heavy fighting and suffered many casualties. There is a monument to them in the French city of La Haye-Du- Puits in Normandy. Robert was likely killed in the Foret de Parroy. This forest is close to Embermenil, France.

I did a pilgrimage to the U.S. Military Cemetery at Epinol, France. I found Robert's grave. There was little on his marker, just dates of his birth and death.

I did a pilgrimage to the U.S. Military Cemetery at Epinol, France. I found Robert's grave. There was little on his marker, just dates of his birth and death. All war is tragic and sad. It is even sadder when a loved one is killed by so-called "friendly fire." Here is a picture of Robert. When he died he was 23 years old.

Albert B. (Bert) Miller and his wife Alice are founding members of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. Bert spent 3 ½ years in the Navy, 1942 – 1945. He completed Midshipman School at Cornell University and in 1944 was commissioned an Ensign in the U. S. Naval Reserve. The same year Bert married Alice (at the time Marine Corporal Alice Hauger), and they will soon celebrate 66 years of marriage. Promoted to Lieutenant Junior Grade during the war, Bert served as Executive Officer of Landing Ship Medium (LSM) 109. After the war, he returned to Cornell and got his B.A. Degree in English. In 1951 he was appointed to the U. S. Foreign Service and a year later became Public Affairs Officer and Vice Consul of the American Consulate in Thessaloniki [aka Salonica], Greece. After foreign Service, Bert worked for Medical Economics, Inc., publisher of Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR), a prime source of drug information for physicians and their patients. For a number of years he was PDR’s General Manager.

I spent five months in the Pacific Theatre. Our ship, LSM 109, was commissioned on November 23, 1944. As ship Executive Officer and Gunnery Officer, I was one of four officers on LSM 109, including the Captain, Engineering Officer, and Communications Officer. We were mainly a transport vessel and carried over 50 Marines into Okinawa.

As I remember, there was some idle conversation as we prepared to land. Mostly the the Marines were quiet and determined. We made a dry landing. The Marines didn’t have to wade their way in with raised rifles. It was an uncontested landing. There was no enemy firing at any of our ships. The Japs were about 50 to 100 yards away, behind foliage—we were later told. We landed troops in about 15 minutes, I think. (This is hard to recall). After all the troops were ashore, we got out of the area. After we got a couple of miles away, we heard the guns. I think it was about two days later when we came back and took wounded out to the hospital ship.

We had six guns, two of which fired rockets. I remember enemy planes flying over us on their way to bomb our destroyers. One time we were throwing up fire like crazy at these Zeros and one went down. I don’t know whether we got that plane or another LSM brought it down. There were three LSMs in the area firing at the Japanese planes.

Our ship earned the American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal. It was decommissioned in 1946. It was sunk 20 miles off the west coast of Florida.

U. S Foreign Service Achievements in War-Torn Greece

I was in the U.S. Foreign Service from 1951 to 1954. Alice and I had an apartment on the top floor of the American Consulate in Thessaloniki. Here’s a picture of the American Consulate in Thessaloniki as it looked in the 1950s. The American flag is waving in front our apartment. The name of the Greek cargo boat in the foreground is “St. Barbara,” which happened to be the name of my mother.

This picture appears in my Greece album containing over 50 photos and several drawings. I wrote an introduction to the pictures entitled “Northern Greece in Black and White”:

These photographs were taken over a three-year period, 1951-1953, when Greece, and northern Greece in particular, was slowly recovering from three years of a harsh German occupation during World War II, followed by 36 months of a bloody civil war with Greek communists who sought to take control of the country.

The civil war (1946-1949) was fought mainly in the villages of northern Greece. With the assistance of the United States military, the Greek Army drove the communist forces northward into what was then Yugoslavia (Macedonia today), a communist country with strong ties to the Soviet Union and ruled by a dictator, Marshall Josip Broz Tito. Albania and Bulgaria, both bordering on northern Greece, were also communist.

The Greek communists who had taken refuge in Yugoslavia were supplied by Yugoslavia. They infiltrated northern Greece through the mountainous regions near Florina in the northwest. Although the war ended in 1949, sporadic and destructive raids on northern villages were launched from Yugoslavia beginning in 1951. The construction of several observation posts and the deployment of border patrols secured the area by the end of the year.

We arrived in Thessaloniki in early 1951 when northern Greece was slowly emerging from the years of destruction and bloodshed. But scars remained, not so much in Thessaloniki and the larger towns far removed from the border, but in the villages in the northwest where most of these photographs were taken.

Some of these photographs, in black and white because color film was not available, reflect the turmoil of the past, as well as recent raids. Others, however, seem to reflect hope, rejuvenation, and the revival of the Greek spirit.

War Victims: Northern Greek women in traditional black mourning clothes, ca 1952

This picture shows a mother and her children in a village near the Bulgarian border. During a communist raid several months before this picture was taken, one of the invaders smashed the mother’s face with his rifle butt. Many villagers were just trying to survive, but they were often caught in fighting between communist and anti-communist forces.

I’d get a little uneasy because there had been so much violence in the recent past. The CIA station in Thessaloniki was right around the corner from our Consulate. The CIA would warn us about the porous border in northern Greece. We had to be careful of communist saboteurs. I never went north without a military escort. If we sensed any communist activity, we’d report it immediately to the CIA.

General Eisenhower stayed a brief time with us. His helicopter was parked on top of the Consulate right over our apartment. He had come to Greece to show strong support for the anti-communist effort and to help bolster Greek Army morale. He was a very nice man. We had a bourbon together. I asked him if he were considering a run for the Presidency. He said, “I’d just as soon not talk about that.” I said with a big smile, “That suggests you might be thinking about running.” He changed the subject; I don’t recall what to.

General Dwight Eisenhower in Thessaloniki, ca. 1951

At the time there was considerable anti-American sentiment in Greece. The leftist newspaper Nea Alithia strongly criticized U.S. policies. My staff and I worked hard to change the newspaper’s attitude toward us. I sat down with members of the Nea Alithia news staff and explained American aims and efforts to help Greece. I took some of their newsmen into the field to show how the Marshall Plan was trying to help Greece get back on its feet. While some Greeks just wanted the U. S. to dole out gifts to them, the best Greeks wanted materials so they could help themselves. They wanted things like farming tools and efficient farming methods so they could produce their own food. There’d been the problem of Greek farmers planting seeds too close together. My staff and I worked with our ag people to who showed the farmers how to plant seeds further apart for better yield.

Eventually there was a marked change in Nea Alithia’s attitude toward the U. S. An example was a positive editorial in the newspaper on September 21, 1952. Our State Department superiors were pleased and sent the Ambassador and Consul General this memo on October 24:

The Secretary and the appropriate offices of the Department have read with interest the Consul General’s Salonika Despatch No. 35 concerning a change in attitude on the part of a Greek newspaper editor wrought through the efforts of the Public Affairs Officer at Salonika, Mr. Albert B. Miller.

Mr. Miller is commended on his clear analysis of the thinking that lay behind the September 21 editorial in Nea Alithia and on his successful attempt by indirect means to put the American aid situation in proper focus.

The Secretary feels that the change in attitude inherent in this incident represents an important accomplishment in our public relations program and is an example of the kind of effectiveness we seek.

Therefore, the Secretary has directed that a Department Commendation be inserted in the personnel file of Mr. Albert B. Miller.

At this time, the Department of State, and the undersigned in particular, wishes also to acknowledge the extremely able and conscientious performance of this officer.

James E. Webb

Things were going well for us in Greece till Roy Cohn and David Schine showed up in my office. You remember those guys?

Yes, quite well! But let’s identify them in case readers don’t know them.

Cohn was a lawyer. In 1951 he’d successfully prosecuted Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for passing highly classified information to the Soviets. Senator Joseph McCarthy appointed Cohn chief counsel to McCarthy’s Senate Investigations Committee. McCarthy and Cohn were on crusade, more like a witch hunt, to find and prosecute communists and subversives in the federal government. Schine was a close friend of Cohn. Schine was also on McCarthy’s staff.

When Cohn and Schine visited us in 1953, they were on a European junket authorized by McCarthy. McCarthy was rewarding them for their work on his committee. He also directed them to sniff out what he thought was communist influence in U.S. agencies overseas.

For about five minutes Cohn and Schine were nice and convivial. Then Cohn said to me, “Tell me what you’re doing to combat communism.”

I told him about our efforts in getting a leftist newspaper, Nea Alithia, to talk more positively about U. S. policies. I also said we were focusing on the Marshall Plan and on projects to enable the Greeks to help themselves.

Cohn said, “Aren’t you showing movies about how wonderful and prosperous things are in America?”

I said, “The worst thing you can do is to show contrast between rich and poor. That’s the best way to get communism moving against us.”

I argued for the soundness of our approach. Cohn and Schine didn’t like it; they left my office in a huff. Who knows what they said when they got back to Washington. They apparently reported me as being soft on communism because the American ambassador told me, “Cohn and Schine checked your entire record at Cornell.” That worried me. I didn’t have anything to hide, but I didn’t want to be dragged through one of McCarthy’s grillings. It looked as if he was going to be in power for some time. My experience with Cohn and Schine was a factor in my decision to resign from the Foreign Service.

McCarthy fell from power in 1954 when the Senate censured him. Ironically, Cohn helped to bring about McCarthy’s downfall. Schine had been drafted in the Army. Cohn tried to get special privileges for Schine. Cohn threatened to wreck the Army if they didn’t give Private Schine an officer’s commission. The Army refused. Cohn and Schine’s shenanigans, McCarthy’s power-mongering, McCarthy’s verbal abuses and unethical tactics—all this finally brought down him and his committee.

A year later, the next Vice-Consul in Thessaloniki, who later headed the Greek desk at the State Department, had access to the personnel files. He told me, “Bert, you never should have resigned.” I was nearing the end of my Foreign Service appointment anyway. Alice and I wanted to get on with our life. I was looking forward to working in a field that was closer to my college major.

The letters about your service in Greece are most impressive. May I quote another one from the State Department?

Sure.

February 9, 1953

Dear Mr. Miller:

Thank you for the highly acceptable and much appreciated story and pictures which you enclosed with your letter of January 14 to the Editor of Field Reporter, Mr. Karl Brown.

We shall be very happy to publish your interesting story about the visit of a U.S.I.S. mobile unit to the village of Karyes. It will probably appear in the May-June issue of Field Reporter. Mr. Brown and I agree that yours is the best written contribution thus far received from the field.

Several copies of the issue of Field Reporter containing your article will be sent to you, as well as a commendatory letter signed by the chief of this division.

Sincerely yours,

Elizabeth C. Drayton

Assistant Chief, Periodicals Section

Division of Publications

Richard (Dick) Newberg grew up in Galesburg, Illnois; has lived in Gainesville, Florida, for a number of years; and now resides at Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. Dick is twice widowed, the father of seven children, the grandfather to seven, a retired CPA, and an avid golfer. His interests also include UF athletics and travel. A decorated veteran of World War II, Dick talks about his combat experiences and English friends he met after the war.

From 4-F to Armored Infantryman

In 1942 I was a sophomore at Michigan State. I tried to enlist. No service would have me. I had high blood pressure, was 4-F. I've always had high blood pressure, 170 over 90, high readings like that. Everybody was patriotic then. Young men were either in military service or going in. I felt awful. I really wanted to do my part for the war effort. All these old ladies would look at me. I could tell they were wondering why I wasn't in uniform.

I was born in Galesburg, Illinois, and raised by my grandparents. Bill Moon was on the Galesburg draft board. I told him I really wanted in the Army. He said, "Don't worry. I'll get you in." I still had high blood pressure but they needed men, so they must've lowered the standards. Same doctor in Chicago who rejected me at Ft. Custer signed my acceptance papers. He thought I was special; he paraded me around in my underwear to show me off. He told me, "You tell the sergeant you shouldn't be out in cold weather." (Laughs.)

Some Army official asked me if I could drive a car. I said I could, so they sent me to Ft. Knox for tank training. After that they put me in radio school and taught me morse code. I went all through the repo-depo [replacement depot] pipeline. You were just a number. Nobody was lower than a buck private replacement. I was one of the troops that went over on the Ile de France, Queen of the French Merchant Marine. We docked near Glasgow. A bagpipe band greeted us. Everybody was shouting, “Go get ’em, Yanks!” I ended up really liking the English and Scots. They personified Churchill’s courage and determination.

General Patton was a colorful man; I saw him twice. I was sent to the 50th Armored Infantry Battalion in Patton’s Third Army just before he ran out of gas. Patton went so fast they had to stop his advance near Metz. The Red Ball Express [combined quartermaster and transportation units] ran from the Normandy beaches to Metz on a two-lane highway to supply Patton with gas. Our unit eventually disembarked at Normandy. My first day with the 50th Armored Infantry Battalion was in the middle of a French field where they dropped me off. We’re the only army I know of that sends men into a war zone individually. Other armies keep soldiers with their units. That way soldiers have a better chance of getting adjusted. Anyway, I was sitting in this field and a Red Cross guy came along in a jeep. He said, “You new here, soldier? Need anything?” I said I didn’t need anything. He gave me a carton of cigarettes. I was very apprehensive about joining Patton’s army. I heard rolling thunder, felt sorry for myself. I didn’t know how a new guy like me would fit in. Thought about having my first smoke! I didn’t realize how lucky I was.

I was getting the cigarettes out when this five-stripe sergeant comes up: Sgt Wloch. He asked if I’d sell him the cigarettes. I said, “Sergeant, I won’t sell you these cigarettes; I’ll give ’em to you.” Greatest use of a carton of cigarettes I could ever make! I was assigned as a radio operator in a half track. We didn’t have any tanks; we rode in half tracks [armored personnel carriers]. You see these Hollywood war movies, and there’s always some sergeant yelling at guys and giving odd-ball orders like get down and gimme 50 pushups, stuff like that. None of that ever happened to me. Never had a sergeant yell at me! Sergeant Wloch and I got along fine. I was in Headquarters Company. I didn’t see any action for quite a while. I had time to learn my job and get adjusted to the guys in the 50th Battalion.

Into the Hell of the Bulge

Eventually we came under sniper fire. The Germans were very skilled at figuring out where our radio transmissions were. They shelled us with artillery, killed the executive officer, and severely wounded the colonel. When the Battle of the Bulge started, my battalion was part of an offensive attacking along the Saar River. We were just about to cross the river into Germany when we were pulled off the line and sent back west to join Patton’s drive into Bastogne. I said “line” but that’s a misnomer. There really weren’t front lines like in the First World War. The lines in World War II kept changing. It was a very fluid situation.

Patton took the 4th and 6th Armored Divisions and started racing toward Bastogne. The 4th Division didn’t stop. I was in the 6th Division. On Christmas Day, 1944 at 9:30 in the morning we stopped for a turkey dinner at Metz, courtesy of U. S. Army rations. Then we got going. We felt when we got to Bastogne we’d be all right. We didn’t think much about dying. It got down to a day’s work. You got up and went to work. You didn’t know what day it was. Every day was the same. What we worried most about was the weather, the cold, where we’d sleep, when we’d eat. There was a routine quality to it. If you dwelled on being shot at you’d crack up.

Patton got to Bastogne in 48 hours. We followed the 4th Armored Division into Bastogne and caught hell. The Germans hit us with small arms and mortars. They had surrounded the 101st [Airborne Division]. The 4th Armored Division punched a hole in the German line. We followed the 4th in and widened the breach in the German line. Man, it was cold. Our left flank was the right flank of the 101st. I was still in 50th Infantry Battalion Headquarters operating a radio.

I heard that English-speaking Germans posed as GI’s during the Bulge.

There was some of that, but it wasn’t very effective. The order came down for us to wear our gas masks on the other side to guard against German infiltrators. The masks had all been thrown away. It was hard to get up Omaha Beach with all the stuff we had to carry so we threw some of it away. Bastogne was finally secured. It cost us 60,000 casualties. I’d see these replacements coming in—cooks, clerks, and others—all part of our big push toward Germany. They hadn’t had much training. They were totally unprepared for what we facing. They weren’t dressed right. They were confused, very scared. I felt sorry for these poor guys.

The 101st found a small tank with a 37 mm gun, fully loaded, ready to go. Headquarters took me out of the half track and put me in this tank. For a while the colonel used the tank as a command post. I drove and Sgt MacIntosh was tank commander. Then it became a reconnaissance tank and we got two additional men. Here’s a model of the tank. I sat on the lower left side driving. The forward gunner sat on the lower right side with a 30 caliber machine gun. Sgt. Macintosh was in the turret operating the 37 mm gun and a 30 caliber machine gun; the other guy with him assisted with the ammo. We were the lead tank in Task Force Ward. This task force was made up of tanks, armored infantry, and armored artillery. One time I got up in the tank turret and looked back. As far as I could see there was a line of armor and artillery. I thought, “What on earth am I doing here?”

Boy Hero of Sommerda

We fought our way into Germany. Outside Sommerda we were stopped by an odd figure. At the time I was some distance away and didn’t see him. Here’s what I heard: this soldier was standing in the road pointing a rifle at our column. He wore a helmet and looked like the long grey coat he was wearing. He was told to surrender but he wouldn’t. He started firing at us. Our guys fired warning shots in the air. An officer said, “Suppose he kills somebody. How am I gonna feel writing that letter to the man’s mother? We gotta take him out.” The medic went down there to check. This soldier was just a boy, 13 years old. The medic came back with tears in his eyes. We wrapped the body up and laid it on the ground off the road. The next morning the body was still there. We called that boy “the hero of Sommerda.”

Silver Star Action

Later we were in the middle of Germany, a few kilometers northwest of Muhlhausen. We’d been under fire all day. We encountered just about every type of enemy resistance, including bombing and strafing by the Luftwaffe. The colonel was pushing us to go, go. We got to the town of Klestadt. An antitank gun started firing over us, raising hell with the bigger vehicles behind us. We pulled into a commune behind a wall. Here comes the colonel in a peep [what everyone in Dick’s armored command called a jeep]. The colonel said, “Boys, you gotta get that gun!” I drove the tank out of the commune toward the German gun. We were going 30 miles an hour, guns blazing, forward gunner shooting the 30 caliber, the sergeant firing the 37 mm. Through the periscope I saw the German gun get hit. Next thing I know we’re stopped dead still. Black smoke all over me! I couldn’t see anything or hear anything. Next thing I recall was picking myself off the ground. I saw two ditches. A squad of American infantry was coming up one ditch. I waved at them. I remember walking with this squad and some captured Germans. This is a picture of the type of Jeb Stuart Light Tank that was my home for most of my combat time in Europe.

We damaged the German gun so it couldn’t be used again except for the shell in the chamber. Some guy pulled the lanyard and the shell went right into us. Here’s a model of a tank I was in. That antitank shell went through here [lower right side], right in the face of the forward gunner. It also killed the sergeant and the other man in the turret. I was picked up by medics who had litters. I had to sit on the dashboard back to the aid station. My face and hair were burnt, didn’t have my helmet or pistol. The surgeon put ointment on my superficially burned face. The men in the aid station were so bad off I didn’t want to look at them. I wasn’t anywhere near being with it. I was really just sitting there. I didn’t ask any questions. One of my MP friends asked, “What’s wrong with you?” I said, “I lost a tank.” We had a shot of cognac. The ambulance came and went back to the hospital without me. I rode back to battalion in the MP peep. I never saw any more action. My hearing never did come all the way back. That’s why I wear these hearing aids today.

I was still a Technician 5th Grade (Corporal). I got to work for an intelligence officer in a Civil Affairs unit at Eisenberg, Germany. Buck, the S-2 sergeant, got an apartment. He, the operations sergeant, and I moved in it. There was a brewery nearby. We had beer and women friends. Man, that was really good duty. It didn’t last long. Russians took over Eisenberg. The Germans sure weren’t happy to see the Russians. We had to move into tents near an airport. I saw Buchenwald: miserable place, shoddy, old wooden buildings, meat hooks in the execution chamber. Some prisoners were still there. We didn’t see any dead bodies. Before the war was over, we were going down a road and saw two emaciated women and a camp of Polish women, farm workers. Barbed wire fence all around the camp! Thirty women hadn’t been fed for some time. The battalion surgeon said, “We can’t feed these women because their bodies won’t tolerate our rations.” For me this was the worst sight of the war.

Making English Friends

My highest rank was Technician 4th Grade (Tech Sergeant). After the war was over, nobody was mad at anybody. I was sent to England and took college courses at Shrivenham American University. I had a professor from Auburn and a professor from Oxford. I met Zeke Copp, my great friend from Michigan State, and every weekend we went to London. We met two English ladies at the Hammersmith Palais de Danse: Joyce, my date, and Florence (Florie) Tame, Zeke’s lady. We had a lot of fun dancing. You went around in a big oval dancing the fox trot. All those romantic songs then: I’ll Be Seeing You, Sentimental Journey, When the Lights Go Out All Over the World, As Time Goes By! I hear them now and I still love them. Forty years later, Zeke tried to look up Florie and got her sister Doris. Her husband Eric got on the phone: “Yank, you’re trying to start World War III. We’ll have none of it.” Zeke finally did get to talk to Florie’s husband Sid. Things warmed up, and eventually we all got together in England: Zeke and his wife Fran, my wife Cynthia and me, Sid and Florie, and Eric and Doris. Over the years Sid came over here six or eight times, each time for a week of golf. Florie died six or seven years ago. This relationship with our English friends added a wonderful dimension to my experiences in Europe.

After the war I married my first wife, Mary Ellen. She had been a Wave during the war. She was killed in an auto accident. Cynthia, my second wife, died five years ago from scleroderma, a widespread connective tissue disease. I graduated from Michigan State in 1947 and went into accounting. My mother became Assistant Dean at Michigan State. My stepfather started the School of Forestry at the University of Missouri. He later took a job in Forestry here at UF. After that he went back to Missouri and headed the department until his retirement.

I don’t regret one single day in the Army. They treated me very well. The GI Bill paid all of my expenses while I was finishing my degree from Michigan State. We used the GI Bill financing guarantees in purchasing our first house. I am satisfied that the Veterans Administration gave and is still giving me state-of-the-art instruments to minimize my hearing problems. Those problems stem directly from my service injuries, but the VA goes further and helps me with my general health and well being. No complaints.

A final bit of irony. When I went back to Michigan State, I enrolled in advanced ROTC with the aim of getting a reserve commission. I did fine in class and was especially competent in the field exercises. However, a physical exam turned up my old blood pressure nemesis and I was asked to resign.

Dick Newberg’s military decorations include:

Silver Star

Purple Heart

Combat Infantry Badge

European Theatre Ribbon, 5 Battle Stars

World War II Victory Medal

Good Conduct Medal

Expert, M-1 Rifle

Expert, Machine Guns (30 and 50 caliber)

Dick’s Silver Star award reads:

By direction of the President and under the provisions of Army Regulations 600-45, 22 September 1941, as amended, the Silver Star is awarded to Technician Fifth Grade Richard E. Newberg, 36699470, Infantry****United States Army. For gallantry in action in the vicinity of****Germany on 7 April 1945. Operating in a light tank, about four hundred yards in advance of an armored column, often under direct observation and through constant enemy fire, Technician Fifth Grade Newberg Demonstrated outstanding skill, aggressiveness, and courage in screening the roads in front of his column. When all other vehicles and personnel sought cover from an enemy anti-tank gun, which was wheeled into a road in the path of their advance, he displayed utter fearlessness and contempt for personal safety, in charging the gun position. He succeeded in partially destroying the gun, killing one of the crew, and wounding several others, before a direct hit completely destroyed his own tank. His action is an epic of gallantry and epitomizes the finest traditions of the United States Infantryman.

|